The Welch Legacy: Rank it, or Yank it?

By Kenly Craighill

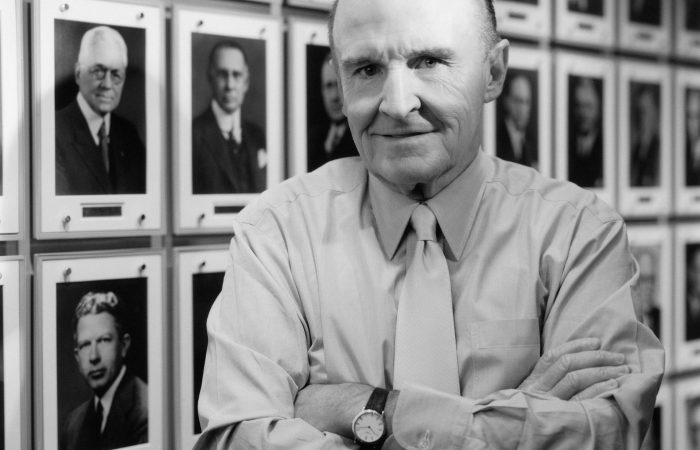

Jack Welch, the “Manager of the Century”, the “CEO of CEOs”, and General Electric superstar died on Monday, March 1, 2020.

After being named the youngest-ever CEO of General Electric in 1981, Welch established himself as the front-runner of a new leadership style: a hard-charging revolution that dismantled General Electric, and aggressively rebuilt it in his own image. He upended GE’s strategy, culture, and decades-long practices. Consistent earnings and soaring share prices made his tenure a model for CEOs worldwide. While at the conglomerate’s helm, he became one of the most widely esteemed, studied, and emulated business leaders on the planet.

Peter Drucker said, “If the Gods want to destroy you, they grant you 20 years of success.” Welch retired in December of 2000 after 20 years at the helm, and set an equal benchmark for his legacy: in his own words, his success would “be determined by how well my successor grows [GE] in the next 20 years.”

Just one year short of that 20-year mark, Jack Welch has passed away—and GE has passed its prime.

Jack Welch was undeniably an accomplished executive. He worked quickly and nimbly, learning from the outdated habits of his predecessors to innovate new business tactics. He ensured GE delivered on its commitment to customers. His energy sparked a sense of urgency in those he interacted with, and his corporate ethos—“fix it, close it, or sell it”—exemplified the unshakeable confidence and decision-making that Harvard Business Review attributes to the most skilled CEOs and leaders. GE’s financial success during Welch’s tenure as CEO is not debatable: the company’s share price rose from $1.27 to $50 per share, four times faster than the overall market. GE’s market cap was $14 billion when Welch took over. When he stepped down, the company was worth $400 billion.

Jack Welch was a phenomenal executive. But an organization’s leader is more than just a decision maker. To leave a legacy they must embody stewardship, especially for an institution as historic, and uniquely vital to America, as General Electric. The CEO of a company is the steward of the brand’s story: not necessarily its creator or owner, but its shepherd, navigating the company forward in a way that is authentic to its purpose, while ensuring the arc of history bends in its favor long after their tenure.

GE’s rich history extends beyond any one person. Originally founded as the Edison Electric Light Company (by Thomas Edison himself), GE is responsible for some of the country’s largest and most ambitious innovations: the first incandescent light bulb, early x-ray machines, the electric stove, America’s first jet engine, and countless other groundbreaking milestones. The company, and the executives that led it for over a century, prided themselves in identifying opportunities to research and develop boundary-pushing products that would define America’s industrial future. In the process, they turned what could have been a faceless conglomerate the world-altering foundation of the modern home.

Even today, few people are untouched by the developments advanced by GE: without it, Americans could have never gathered around the radio for the first live voice broadcast, received the life-saving care made possible by MRI machines, or taken that “giant leap for mankind” during the 1969 moon landing. Leadership in industrial innovation has allowed GE to endur two World Wars, the Great Depression, and other crises that wiped out even the most resilient organizations.

The CEO of GE is the steward of an organization and a story that is woven into the fabric of America itself.

When Welch ascended to the corner office, he had a different GE in mind. Rather than “building upon past innovation to drive innovation for the future,” Welch built upon one of the largest and most significant bull markets in American history to emphasize quarterly profits. The 1980’s measured corporate success in one metric: stock performance, and with the wind of a strong economy in his sails, Welch focused on those measures in lieu of GE’s historic pride in product development. His top priority was growing GE’s stock prices—and he did anything he could to achieve that goal, even if it meant putting his shareholders before the innovative story GE had trusted him to care for.

To attain the financial growth he promised those shareholders, Jack Welch demanded a culture shift that motivated employees to become aggressively competitive. He implemented his famous “rank or yank” program, a practice that established a performance-based hierarchy, culling the bottom 10 percent of the workforce annually. His ruthless tactics earned him the nickname “Neutron Jack”, a reference to neutron bombs that would destroy people but leave buildings intact. Though this strategy allowed Welch to achieve his financial goals by identifying the most competitive workers and restricting the pay of those who fell below that mark, it was extraordinarily contradictory to GE’s history in product development—it’s widely believed to discourage innovation, as employees are far less likely to pursue an ambitious project with the fear of potential failure.

GE’s own founder, Thomas Edison, who once claimed “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work,” would not have had a place in Jack Welch’s organization.

Welch’s ranking system implemented a culture that markets loved, but that deprived GE of the innovation that historically fueled its success. Absent the next great American industrial innovation, Welch sought growth in one specific business, tangential to the story he was shepherding: GE Capital.

Pre-Welch, the division’s primary purpose was to underwrite loans for GE products. It became a black box from which Welch consistently pulled money to meet and exceed Wall Street’s quarterly estimates, a tactic that used pennies per share to further solidify shareholder confidence in the company—and prop up prices. The financial services and risky loans offered by GE Capital became the primary driver of the company’s financial performance: by 2002, 40 percent of GE’s revenue was a direct result of GE Capital. While offerings such as life insurance and credit cards ensured consistent quarterly performance and corporate praise for Jack Welch, GE drifted from its identity as an industrial manufacturer.

Welch dismantled an identity formed over more than a century: one that previous GE CEOs had perpetuated, respected, and shepherded. Yes, the company was made money under Welch—a lot of money. But that performance eclipsed GE’s story, and drained the company of a driving purpose. And ultimately came at a long cost that undid all of those short-term gains. When Welch resigned in 2000 he left a clear track record of prioritizing what was best for shareholders in the short-term, with utter lack of regard for his role as the company’s shepherd.

The impact of this approach is evident in Welch’s own 20-year standard.

Welch’s successor, Jeff Immelt, followed in his predecessor’s stock-focused footsteps. When the 2008 financial crisis tore through the country, GE nearly toppled—the company’s stock, the benchmark Welch prized so dearly, fell 42 percent over the course of the year. America’s “most well-managed company” was suddenly pressed for cash, and more than $200 billion in value had essentially vanished. The core of these problems? Bad loans at GE Capital. The legacy Welch left for Immelt crystalized: “the house Jack built” was forced to cut its dividend payments by two thirds—the biggest single dividend cut by an American company ever. GE Capital required a $139 billion bailout from the federal government. Welch had shunned his obligation to shepherd the story of the organization, and the new one he had crafted was bankrupt, as well.

In attempt to resolve the crumbled brand story, GE sold off much of GE Capital—$275 billion worth of services line—and recommitted the company’s primary revenue focus to its industrial and manufacturing arms. It aims to ensure manufacturing makes up 90 percent of its business, but it has a long way to go—those components of GE still only comprise 58 percent of the organization.

“As we grew,” Immelt said, financial services became too big and added too much volatility. GE must be an industrial company first.”

Immelt required 16 years as CEO to realize his role as a shepherd of the brand story. A third leader, new CEO John Flannery, will be the one to lead GE past Welch’s 20-year benchmark. He hopes to “make some major changes with urgency and depth of purpose,” but it will take years to rebuild what took over a century to establish, and only a decade to shatter.

Welch said it himself: his success would be determined by how well his successors performed in the 20 years after his retirement. GE lives on, as do the legacies of its CEOs. With Welch’s passing, others must answer his own essential question: did his stewardship of GE ultimately rank or yank?

Kenly Craighill is an associate at Woden. Want to stay connected? Add Kenly on LinkedIn, read our extensive guide on how to craft your organization’s narrative, or send us an email at connect@wodenworks.com to discuss whatever your storytelling needs may be.