That New HQ Isn’t For You

Gilded Corporate Palaces Are the Ultimate Rejection of Customer Focus

By Ed Lynes

One of the nation’s most prominent tech companies is in the market for a second headquarters. They’re based on the West Coast, start with the letter “A,” and have a brand that simultaneously delights their customers and frightens their rivals: Apple. They are undergoing a quiet, deliberate search for space to house more new employees. It hasn’t been front-page news — and maybe that’s because Apple has learned a messaging strategy built around the corporate headquarters isn’t all its made out to be.

The growing company recently opened its long-awaited “spaceship” campus. While the accolades about design have piled up, the HQ’s development has paralleled with a number of uncharacteristic missteps. Reports have noted that Jony Ive, Apple’s design leader, has been spending more time on the campus itself than products. Public reports indicate he’s not involved in this next HQ project, which is probably for the better: deploying your most valuable resources on your own office space is the opposite of customer-centric thinking that Apple claims to embody.

Hop a flight, and just a few hours north, there’s another member of the “GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon) Four” undergoing their own headquarters search. Not to be outdone by their Cupertino rival, Amazon has turned their new HQ process into a reality show that makes the descriptions of custom curved glass from Apple seem tame. Amazon’s search for a second headquarters dominated tech and municipal news through the end of 2017, and cities have fallen over themselves to court Amazon and its planned $5 billion of investment in a new home.

Amazon recently released the list of the top 20 cities who are finalists, and no surprise: Stonecrest, Georgia didn’t make the list. The current contenders are entirely expected: Boston, Atlanta, Dallas, Washington, New York City, and the like. Woden team member Mary McCool has effectively written about the folly of thinking “all publicity is good publicity,” and Amazon’s showy, drawn-out selection process has pressed their luck in this regard. Their insistence on gobbling up free press that actively undermines their brand story is ready to boomerang right back at them.

Before conducting an office search that feels like an urban beauty pageant, Amazon had to grow to the point where it was in need of a second headquarters. For twenty years, it has endeared itself to customers with one simple promise:

At Amazon.com, it’s our goal to be Earth’s most customer–centric company, where customers can find and discover anything they might want to buy online. We strive to offer our customers the lowest possible prices, the best available selection, and the utmost convenience.

It’s clever. Great brand messages are not about any particular product, and speak not to features and benefits but to the underlying purpose behind the brand. Of course, what you do is even more important than what you say: messages must be rooted in authenticity and lived daily.

When Jeff Bezos was packing books in his garage, he had a vision for delivering much more, and deftly built his company’s promise not around the books, but the convenience of delivery and an incredible selection of goods. Amazon made purchasing anything frictionless, and established the still gold-standard of customer service in the Internet age. Request anything from Amazon.com, and they will have it on your doorstep the next day.

Every time Amazon grew, it looked for a new market where endless choice coupled with speedy delivery would enrapture customers: books, video, groceries, pet products, home goods, and now, truly, everything from A to Z. With each new acquisition, Amazon also became better at selling consumers what they want most. Targeted ads based on shopping behavior were a start, but now devices such as the Kindle or Alexa ensure Amazon is collecting data on every move customers make to offer customized deals at the exact right time.

Like other members of the GAFA Four, these ever-expanding tentacles into people’s lives come with risk of blowback. Google and Apple have seen their fair share of customer frustration, and the results of the most recent election have led to difficult conversations about how much Facebook truly controls what people read, believe — and even think. As these companies are ever more successful and powerful, the need for them to truly embrace their customer-centric philosophies matter.

When consumers feel the GAFA Four is wielding their incredible power to improve daily life, it feels wonderful. But once those same people start to feel incidental to the company’s goals — that their data and eyeballs are just a product, that they exist for the benefit of the corporation and not vice-versa — the arrangement feels much more sinister.

Two hundred thirty-eight municipal governments around America spent millions trying to woo Amazon — Philadelphia spent $245,000 alone. Millions of these dollars were spent by towns that never had a chance, yet who diverted valuable funds from schools, first responders, and community initiatives for a chance to play the lottery. It’s too bad no one told them it was rigged from the start — based on the list of finalists, did Detroit really ever have a chance?

Amazon’s fully to blame for this. Virtually all large companies conduct their headquarter searches out of the public eye. It allows for discrete conversations at the municipal level, and allows both the company and government to negotiate a package of incentives that makes everyone win. Most practically, it keeps the company’s story and focus on its customers, rather than on themselves. GE’s relocation to Boston is a an example of how this type of search can benefit everyone: by the time the agreement was public, it was a narrative of partnership and mutual investment.

By encouraging American governments to whore themselves out, and subsidize their search, Amazon has tipped its brand narrative from one of consumer-focused convenience to one of me-first capitalism. The trade-off for low pricing is your tax dollars — delivered tomorrow, if you join Prime today.

If this whole experience feels strange, it should. While Amazon is notorious for plowing its profits back into growth, it’s making more money than ever and is number 12 on the Fortune 500. Contrast that with the cities falling over themselves to subsidize Amazon, many of whom are on the verge of fiscal ruin. Amazon doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Those precarious municipalities and their taxpayers are the customers they profess to value so highly, and the leadership needs to balance its responsibility to the bottom line with the obligation to establish lasting value among its audience.

The world’s “other” big retailer might offer counsel to Amazon: exercise caution in your desire for taxpayer dollars. They may never move from Bentonville, Arkansas, but Walmart is well known for leveraging the government as a subsidy for its business. Interestingly, the core of the Walmart brand promise is stunningly similar to Amazon’s: low prices and incredible selection. Yet, despite having lower prices than Walmart, Amazon has managed to capture the cultural mainstream, while Walmart’s customers remain less affluent and the brand less valued.

Walmart has long faced criticism for the way it uses food stamps and other government subsidies to maintain its profitability. These sustained attacks on the Walmart brand weren’t immediately successful, but over time the image of a profitable company exploiting workers, governments, and customers has taken its toll. Stories abound of Walmart shirking responsibilities to the communities where it maintains a presence, and the public perception of the brand has slowly eroded accordingly.

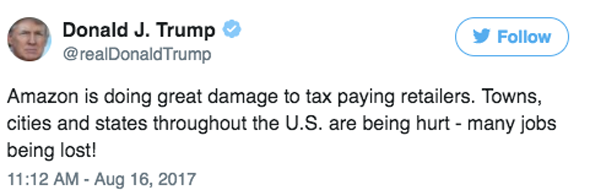

And, of course, the blowback has already started. America’s Tweeter-in-Chief has made Amazon a convenient target for all that’s wrong with the American enterprise system. Those criticisms may not resonate immediately in the Pacific Northwest, but as a company whose consumer footprint is almost entirely American, it’s not good business to be in the President’s crosshairs. More concerning is not the damage these comments might cause, but rather what they could be a harbinger of.

It’s time for Amazon to get things back on track. The free publicity around the search may have seemed like a good idea in a vacuum, but with the experiment run wild, it’s time to bring the search back in-house for those Top 20 cities, and make a discrete decision, with an eye to what is best for Amazon’s customers. In planning their own search, Apple CEO Tim Cook noted it was designed to “prevent this kind of auction process that we want to stay out of.” Combined with Ive’s refocus on consumer products, it appears Apple may have learned from their new HQ — and Amazon should heed the lesson.

In the meantime, Amazon has done real damage to its brand story. While this is certainly an opportunity for Walmart’s Jet.com to move ahead, Amazon should stay on the offensive. Double-down on the promise that’s brought them to this point: keep customers, and the things they want, front and center.

A little humility might help, as well. The GAFA Four have earned some hubris, but if Amazon wants to continue to be successful, it needs to keep the focus on empowering its customer, not itself. Amazon should remind people how great they can be (if they sign up for Prime today — only $99 per year, and did you know your subscription includes Prime Video?).

Consumers accept that an increasingly smaller number of companies influence their daily lives, and that there’s a tradeoff for those wonderful advances. But shared purpose with a company like Amazon is what makes that palatable. Living the consumer-focused story is what makes that reasonable. Placing cities in bitter, public competition for Amazon’s largesse is dangerous because it calls into question their commitment to the core brand promise — and the consequences of that are terrifying to consider.

Once shared purpose between a company and its customers erodes, the company becomes yet another soulless corporate behemoth, and emerges as a target for rejection — and disruption. And that makes it more likely other cities will become wise to what Seattle already knows: hosting a company like Amazon isn’t all its made out to be.

Ed Lynes is a partner at Woden. Whatever your storytelling needs may be, Woden can help. Read our extensive guide on how to craft your organization’s narrative, or send us an email at connect@wodenworks.com to discuss how we can help tell your story.